[#70] Biometric authentication for payments is having its moment, but will it actually move the needle? (Spoiler: In India, probably not)

The marginal benefit of biometric auth in experience over PIN / OTP, issuer banks lethargy, 3rd party orchestration sign-offs and government repository challenges may restrict it to a "cool concept"

So, something that I’ve been tracking for the last 6 months is new ways of authenticating payments. This has also been a topic of discussion for Kaustubh Adhikari & I (Engineering Manager @ Constantinople); we’ve debated this out a lot, and it is something we’ve worked on together as well.

So when biometric & alternate authentication started gaining hype, naturally I was quite excited. And there has been a lot of news around biometric authentication in the last few months, Ex:

Minkasu Pay in partnership with Federal Bank launches biometric auth as a method to authenticate payments. Minkasu Pay is a start-up HQ’ed in California. It was founded in 2015, and raised seed funding of ~$1M in 2016. It was granted a patent for its 2FA biometric payment authentication in India in 2024.

NPCI announces biometric authentication on UPI as one of the key innovations being focused on (alternate forms of authentication on UPI - things such as silent mobile verification, with Sekura & Bureau as partners, and biometric authentication is actually something I worked on during my Razorpay days, so this is something that is super close to my heart, and just as a topic is something I think about a lot, so if anyone reading this is doing something here, please do reach out, I’d love to learn more)

Authentication is having its moment.

Over the past two years, it's become one of the most talked about themes in payments largely driven by new authentication methods being rolled out by networks like Mastercard and Visa. From palm to facial recognition, biometric payments are no longer just experimental; there are pilots being rolled out and every payment method seems to want to get involved in this some how.

Looking at some of their strategic moves over the last year (and this is something that I’ve written about in the past) , it’s clear that authentication and more broadly, credential based identity verification is one of the biggest bets these networks are making. But why is this even a conversation? Why are “alternative forms of authentication” becoming relevant now?

To answer that, we need to understand how payment authentication works today. I wrote a piece on this a few months ago, which you can check out below:

[#59] From Card Networks to Credential Networks: Visa & Mastercard’s Next Big Move?

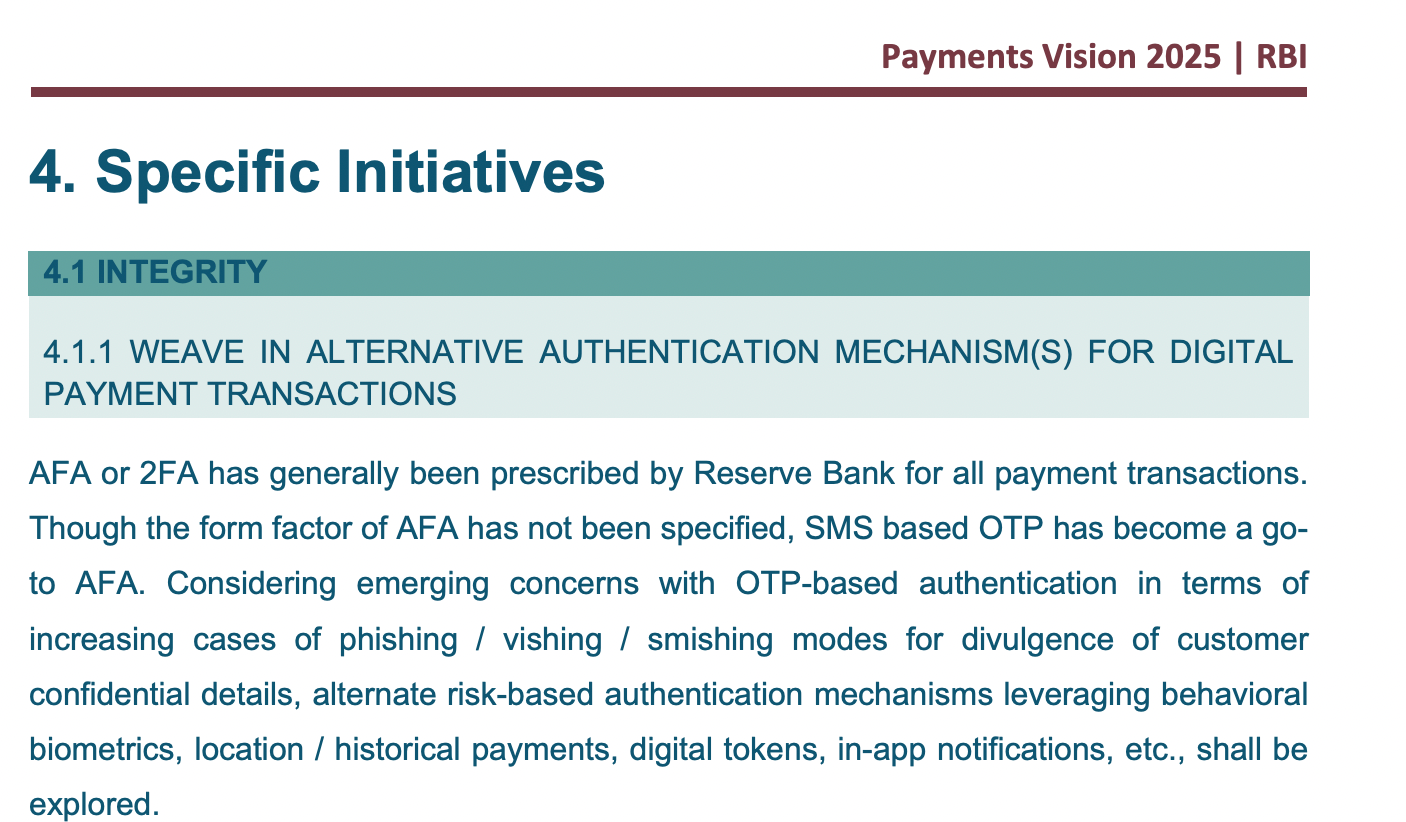

So I recently read RBI’s FY25 payments vision. RBI’s FY25 payments vision talks about weaving in alternate forms of authentication, and moving away from OTP based forms of auth, because of general risk related to phishing, and release of confidential customer details. So I generally expect a lot of authentication based innovations, both from existing an…

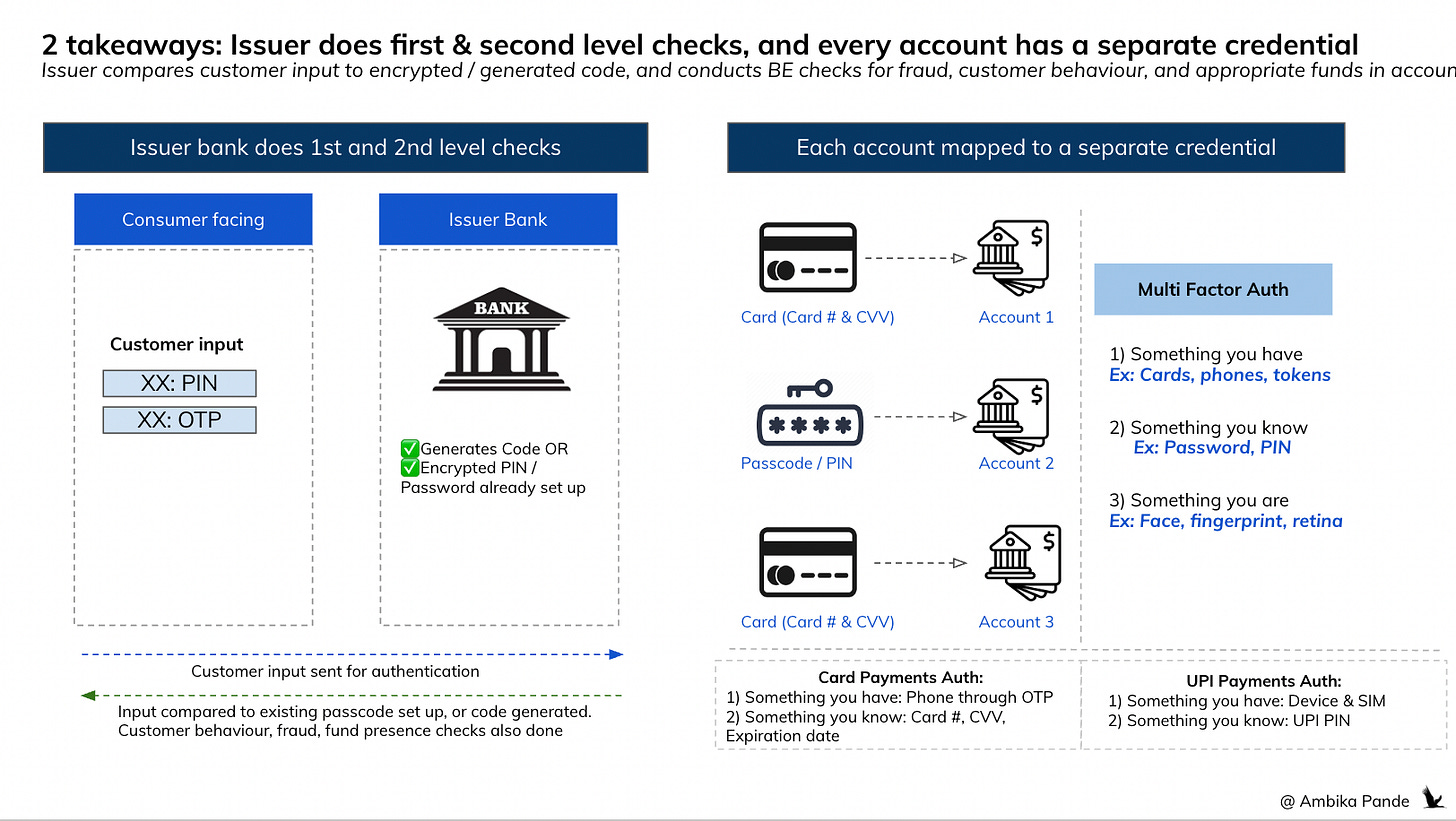

2 Factor Authentication (2FA) in India is mandated by RBI, which is why you have to use your OTP + Card details, or your device + PIN in the case of UPI to authenticate payments

Payment authentication is different for cards & UPI, and other methods, but overall, the flow of customer information remains the same: in its current form, all authentication, both first level (customer input) and second level (fraud, customer behaviour checks) are done by the issuer bank. Also, there’s a concept of Multi Factor Authentication. And in India, 2FA is mandated, 2FA stands for 2 Factor Authentication, which means that 2 factors out of the multiple ways to authenticate need to be authenticated for the payment to go through.

Multi Factor Authentication:

1) Something you have: Phone, Device (or OTP - since this comes to the device)

2) Something you know: Password, Pin

3) Something you are: Face ID, fingerprints, retina scan

All the existing and newer authentication processes (atleast for India) will have to meet 2FA. Cards for example handles 2FA through:

Something you know: Card number, CVV &

Something you have: Device (which receives OTP).

Now, the problem that exists with the “something you know” bucket is that there is still risk of fraud

We’ve all seen how passwords and OTPs which were once considered secure have now become susceptible to fraud. Passwords get leaked. OTPs get phished. And most of us know someone who’s fallen for the classic scam: a caller pretending to be from the bank says there’s a problem with your account and asks for the OTP to “fix” it. Moments later, the victim’s account is emptied.

RBI’s Payments Vision for 2025 explicitly acknowledges this problem. It clearly states the need to move beyond OTP-based authentication methods. I’ve been seeing this shift play out on the ground over the last few months. Globally too, payment authentication is undergoing a major rethink, with growing emphasis on stronger, more seamless alternatives.

So biometric authentication at least conceptually seems to be way more secure than the OTP / password based system. It’s hard to fake “who you are.”

What do the current payment auth mechanisms look like?

To understand what biometric payments are solving for, and the issues / benefits of this, lets first understand how payment authentication currently works.

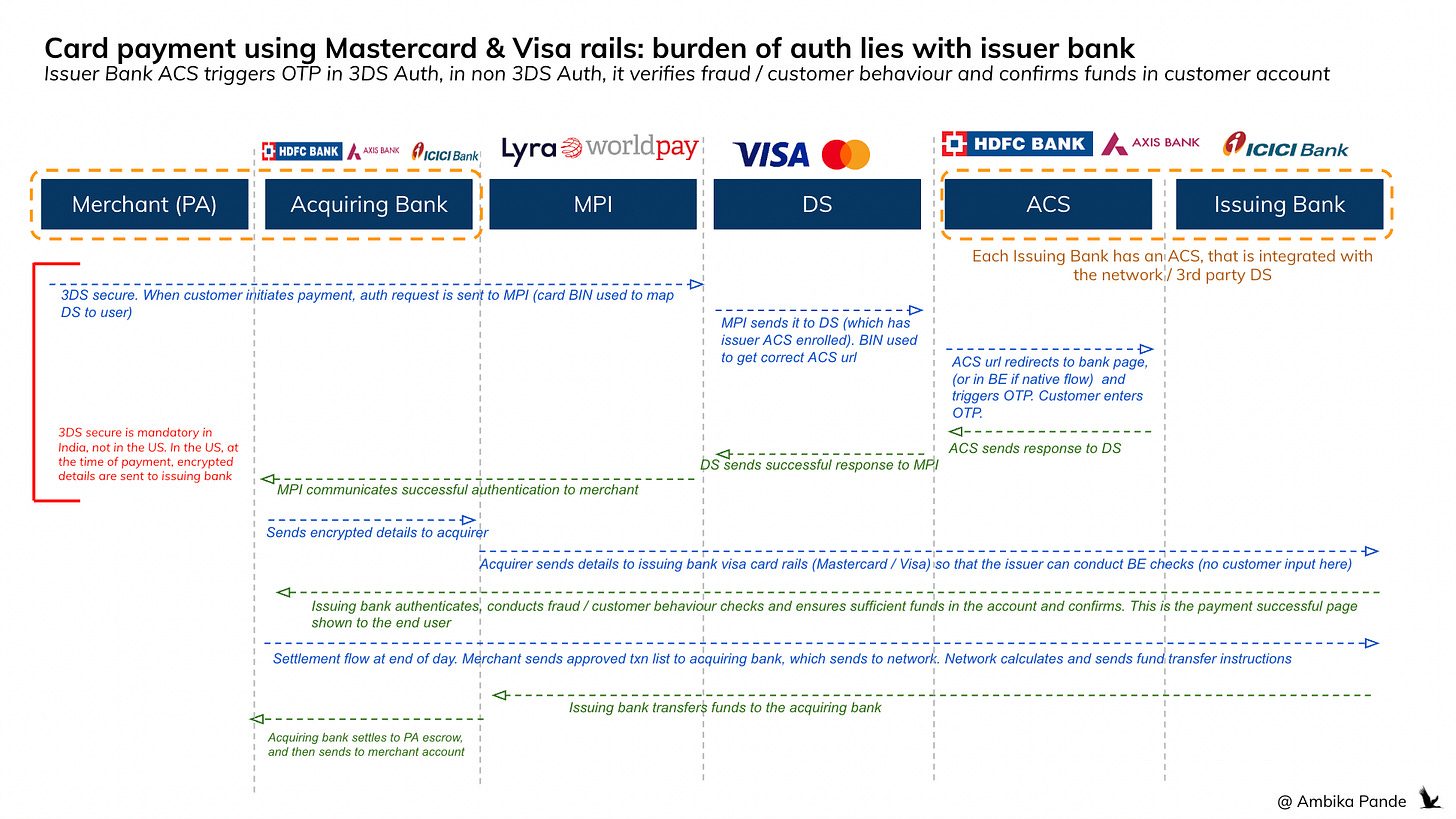

Cards - Payment Authentication

This is the step that confirms that the user is who they say they are. It’s different from authorization, which is more around - can the user actually transfer the money, after they have verified who they are

The user chooses to pay by card at the merchant checkout

For merchants / geographies where 3DS secure is mandatory (this is the OTP step in India), the merchant sends the auth request to the Merchant Plug-in (MPI).

Think of the MPI as a piece of tech that connects the merchant to the Director Server (DS)

The Directory Server is a 3rd party database which contains the mapped card numbers to the appropriate ACS of each issuer bank. Each network (in this case: Mastercard, Visa etc has its own DS)

The ACS is the Access Control Server. Each issuer bank has its own ACS. This is integrated with the 3rd party DS, or the network DS. The ACS is responsible for triggering the OTP to the mapped customer number with the card

The customer card BIN number (first 4-6 card digits) are used to identify which DS to send to (aka which network the card belongs to).

At the DS, the card number is mapped to the issuer bank, and the ACS url of the appropriate bank is sent.

The ACS of the issuer bank maps the customer card number to the phone number, and triggers the OTP. The ACS can either be built by the bank, or can be a 3rd party provider. Fintech’s as a part of the full stack play are all getting in here also.

The ACS url redirects to the “bank page” where you’re redirected to, where you enter the bank OTP. There are also native flows, where the url triggers the OTP in the backend, and the end user can enter the OTP page in the embedded journey.

Once the user enters the OTP, either on the bank page or the native experience (on the merchant page), then the ACS generates an auth result, which is can be Yes, No, or some intermediate / pending stage.

The ACS then communicates this to the DS, which confirms this to the merchant through the MPI. This is the end of the authentication steps

Cards - Payment Authorization

After confirming the user is who they say they are, this step confirms if they CAN transfer money. This depends on if there is money in the account, if no transaction limit has been expired and so on.

After the successful OTP authentication is done, then the merchant communicates this to its acquiring bank, which sends an authorization request to the network, which then sends it to the issuer bank

Issuer does the back-end checks (fraud, account balance etc)

The issuer sends a response back to the acquiring bank through the network to confirm authorization

This is then sent from the acquiring bank to the merchant, and this is where the “payment successful” now shows to the end user.

Cards - Fund transfer & Settlement

The funds transfer for cards happen at the end of every day. The merchant “batches” all the approved transactions and sends to its acquiring bank.

The acquiring bank sends it to the network (Mastercard / Visa). The network then puts it through its clearing and settlement system, which calculates the net payable to each party and initiates fund movement instructions

Issuer sends the funds to the acquiring bank

The acquirer bank then settles this to the merchant account (sans the MDR), this usually is T+1 in India, but can go up to T+2, T+3, this is usually the designated settlement time in the geography.

Note: this OTP step is only in India where 2FA is mandated (something you have - OTP = device / SIM). In countries like the US, 2FA is not required.

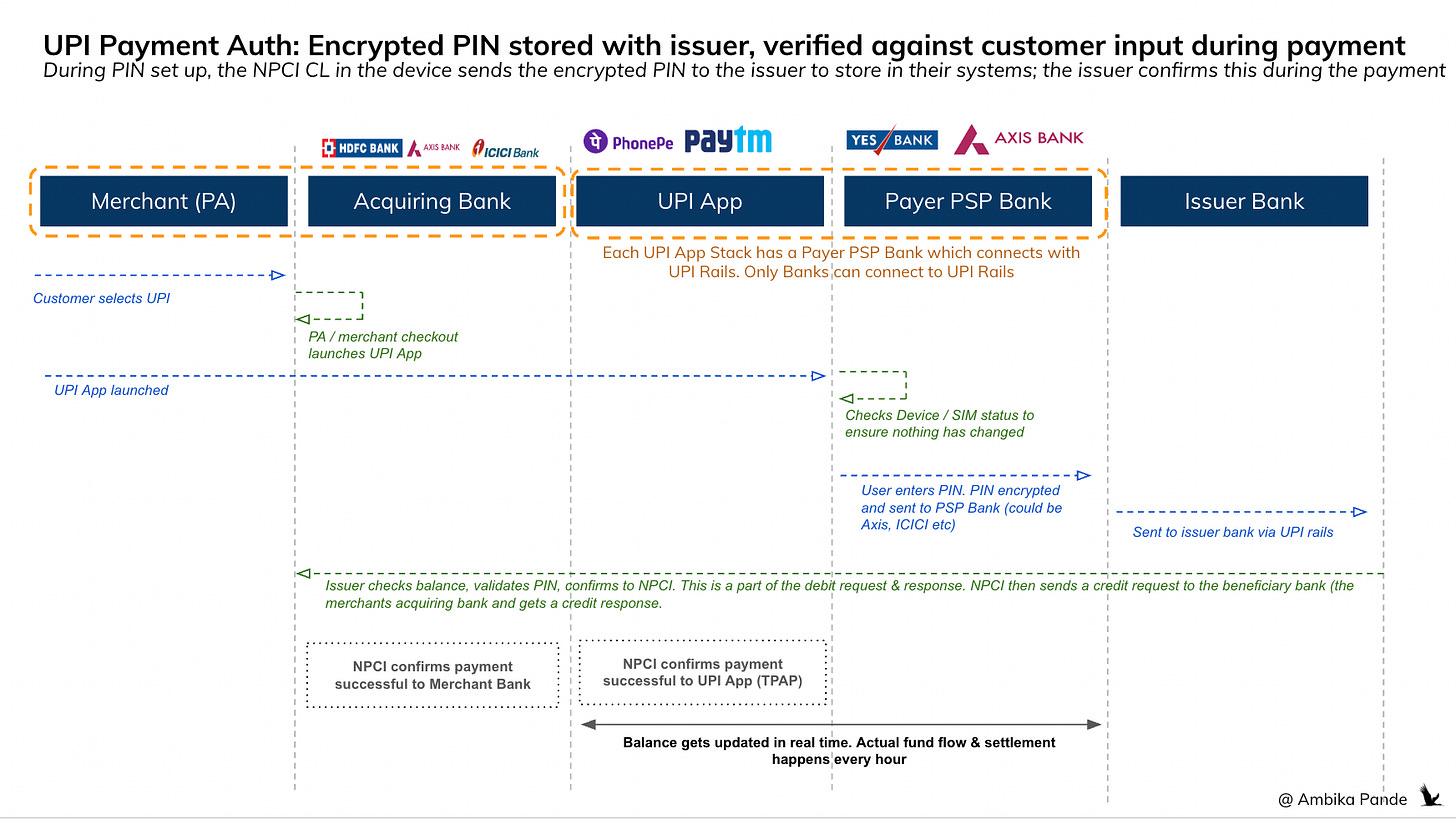

UPI - Payment Authentication & Authorization

This is different from cards, where there is nothing to set up. In cards you have to enter your CVV and tokenize your details one time. After that it gets authenticated through OTP. UPI requires a 1) device binding step (something you have) and then a 2) PIN set up step (something you know)

Device binding step

The user comes into their UPI App (PhonePe, Paytm, Googlepay etc)

There is a step where you “bind your device” to that UPI App. This takes care of the “something you have” step in payment authentication.

If you folks have downloaded a new UPI app, you have to send an SMS - if its android then it is automatically sent, but if its iOS, then you have to manually send it. In the backend, what is happening is that the the app reads the device SIM, and creates an encrypted payload with the SIM details, device details, App details & mobile number. It then sends this to a predefined number controlled by the PSP bank.

Note: There are alternates to even this step coming in. Silent Mobile Verification (SMV), also known as silent OTP or silent SIM verification, is amethod used to authenticate a user’s mobile number without OTP. The user enters their mobile number into an app. This number is then sent to a telecom provider. The telecom provider returns a naked url which the mobile app hits. The telco captures key identifiers from the device and network, such as the MSISDN (mobile number), IMSI (SIM identifier), IMEI (device ID), and MCC/MNC (country and operator codes)from the network headers. These details are then validated by the telco to ensure that the SIM card currently in the device matches the mobile number provided by the user.

The PSP bank receives the payload from the mobile number and compares it to what was expected in the payload that was created:

The mobile number the SMS is being sent from, and the encrypted number in the payload need to match.

The App details are present to highlight which app this request is coming from, and that it is linked to the PSP Bank

The device details are stored later, this is sent in the payload to start building the device fingerprint

Once the SIM & App are verified, the device details are stored against the SIM details by the PSP Bank locally.

After this, the end user selects their account to link to UPI. This is usually a page where the user has to select their bank from a list (if they have never linked that account on UPI).

After the user selects their account, the PSP confirms it, the VPA is created which is abc@oksbi for example.

This VPA is stored with NPCI in the UPI Mapper, which maps the mobile numbers to bank accounts, and the VPA handles to the bank accounts. This is how you’re able to send money to a mobile number: at the backend, NPCI is resolving and mapping the mobile number to the relevant bank account

PIN set up step

After account selection, the PIN set up step kicks in

When you go to the PIN set up page, you’ve probably seen that page that opens up where you have to enter your 4 digit PIN. This is something called the NPCI Common Library (CL) that is part of the mobile app SDK. (Note: this is also why UPI only supports mobile based payments currently, you cannot authenticate a UPI payment through a browser because it is so tightly coupled to your mobile device).

The CL is responsible for encrypting the PIN and sending it to the issuer bank for storage. Then the next time when the end user comes to authenticate the payment, the CL sends the PIN entered to the issuer. The issuer decrypts, compares, and then sends the authentication confirmation

Authentication step after PIN has been set up

The user comes in to the merchant checkout and initiates payment. The PA loads the UPI Apps on their checkout page

The user selects the UPI App they want to pay through

The UPI App checks whether the device & the SIM is the same:

At the time of set up, the UPI App stores device details in local storage, and compares what is stored with the PSP Bank to local storage. If anything has changed, then binding is re-triggered

Checks if SIM is the same

When they open the UPI App (through a smart intent flow), this prompts them to proceed with payment.

When they proceed, they see the PIN entry page. This is the NPCI CL.

When they enter their PIN, the CL encrypts this and sends to the issuer via NPCI rails (using the NPCI UPI Mapper)

The issuer confirms the PIN, checks txn limit, balance check etc and sends confirmation to NPCI, which confirms to both the beneficiary bank (the merchant bank account) as well as the PSP Bank of the UPI Bank

UPI - Fund Transfer & Settlement

Settlement happens in batches - usually hourly. While the balances are updated in real time, the actual money movement happens every hour by NPCI, where they calculate the net debit & credit to each bank, and move funds using RTGS accordingly

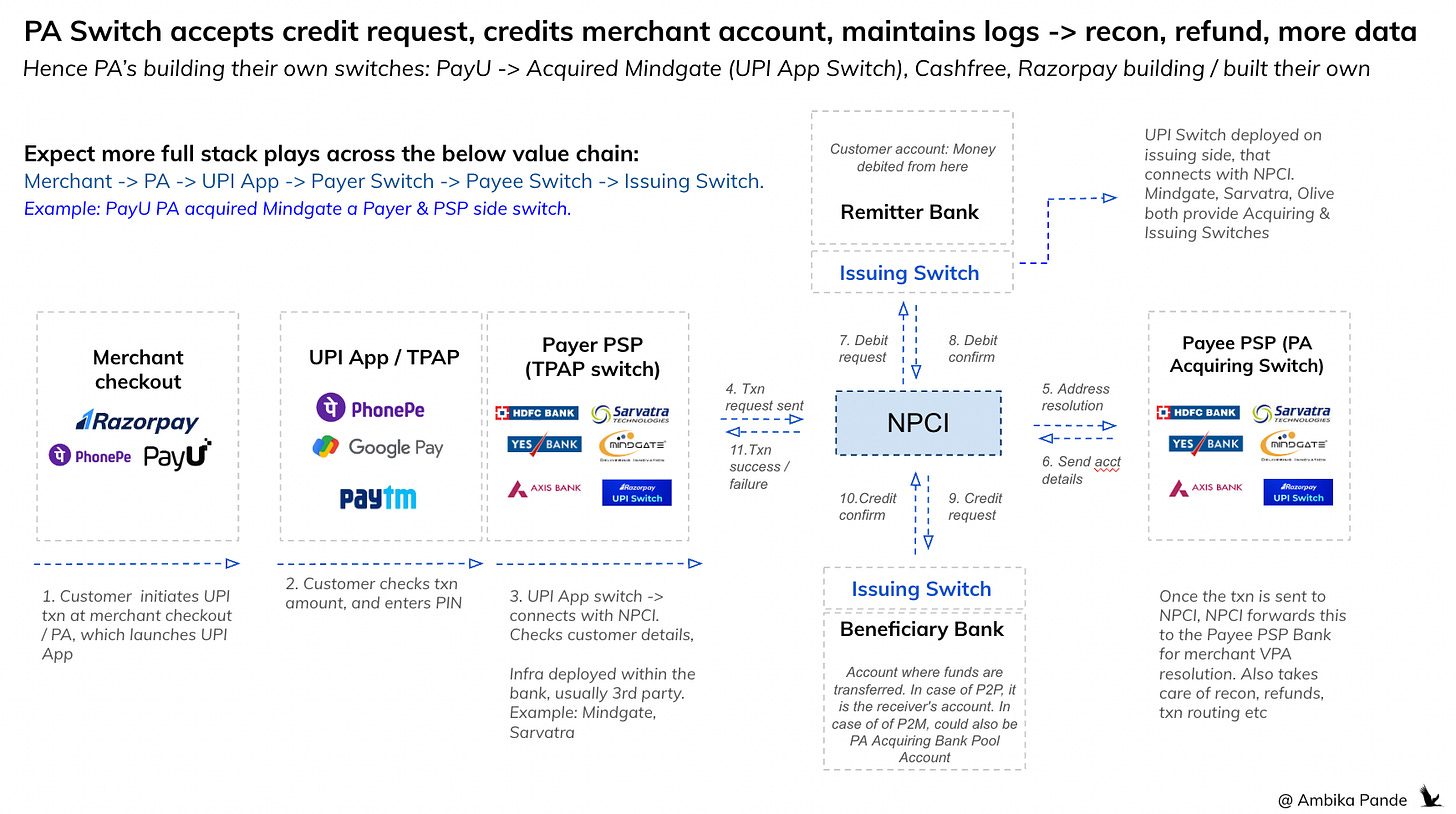

Note: The PSP switch here is the UPI App sponsor bank. In other articles, I have talked about the PA UPI Switch, and the merchant acquiring bank. In a UPI world, both can be the same. Example: the payment gets initiated on merchant checkout. When you go to your UPI App to pay, you’ll see a handle: something like zomato@icicibank, or zomato@rzp.xxbank. This is the acquiring bank. In the case of rzp.xx bank, this is a custom switch that is deployed by razorpay at xx bank. This switch accepts the credit, credits the merchant account (in the PA records) & maintains txn logs, which checks against NPCI files, and issuer bank responses It also ensures there are no missing credits, duplicates, or mismatches. It also generates daily reports and settlement instructions. And if discrepancy is found, the PA raises dispute/recon claims. This is why PAs are actively building and owning these acquiring switches, it allows them tighter control over the flow, data, and reliability of UPI payments. The switch becomes the nerve center of credit intake, reconciliation, and merchant settlement, traditionally the role of acquiring banks, but now modularized and productized by fintechs. But this is a separate topic.

Now, both explanations were long winded but this is important to understand what roles each entity is playing in authentication & authorization. Some key takeaways:

1. One credential per account NOT bank:

Currently it’s not that you have 1 bank card, which counts for all your credit, debit and anything else. Each account has a separate card, (credential), a separate CVV, a separate number, and you authenticate at an account level, not a bank level

2. All first level authentication happens by the issuer bank

Whether this is the PIN, the password, the OTP. Either it is stored with the issuer bank, in the case of UPI PIN, or the OTP is generated by the bank (or a 3rd party provider for the bank). The bank is not “believing” a success response sent by a 3rd party, it is authenticating the credential itself

3. The network acts as a rail that issues instructions and routes funds, but doesn’t make any decisions in authentication or identity verification

The network connects the banks, does calculations on how owes who how much, issues fund movement instructions, and does reconciliation. It’s not playing a role either in the fund flow, or in the authentication itself. There’s no decisioning happening at this step, where it says: “Hey - this user is who they claim to be.”

That is what seems to be changing now. Mastercard & VISA want more ownership of this step

They’re doing this in two ways:

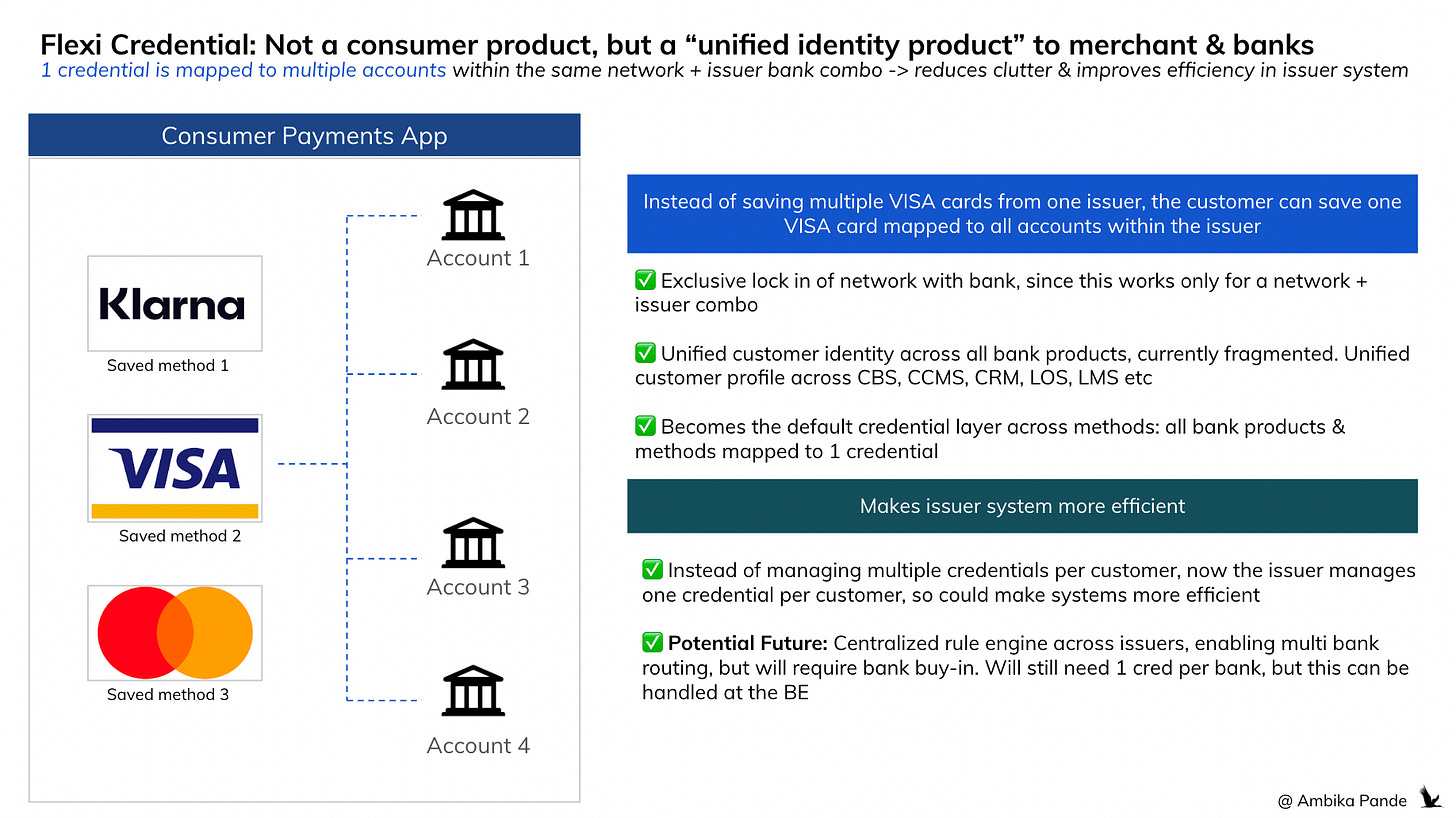

1) Flexi Credential / One Credential for all accounts for same issuer + network combination → real play is credential network for merchants & banks, it isn’t a consumer product

Instead of having 1 credential per account, Mastercard & Visa are now saying that hey, we’ll give you one credential per bank. So for a user who has an Axis + Mastercard combination, they will have the same credential for their credit, debit, or any other product they get from the bank.

Now, I’m unsure of the value add here to the end customer, but for the network, it seems to be a way to get in deeper into a bank. It can also make issuer systems more efficient, instead of mapping multiple credentials to one user, it can maintain a much more efficient mapping. Something I’ve also talked about before is the fact that traditional banks really struggle with the “one customer” view because there are different systems using different identifiers for one customer. This could help solve that and eventually give banks much richer data to better personalized experiences and cross sell products. You can read about that here: #64 Innovation at the edges, stagnation at the core: Why India needs neobanks for true financial inclusion. So the real play here is not for the end customer benefit. That is just where it is easily visible.

This is actually a play for the CRM & customer identity management, where Mastercard or Visa become the default identity layer authenticating payments & anything else

Even in the case of UPI, if this play by the networks works out, Visa / Mastercard could play a role in mapping the UPI VPA as one of the many endpoints to the unified customer credential. Other end points could be credit accounts, BNPL, or any other type of method.

2) Through Passkeys: Mastercard / VISA use biometric auth for payments, the public key is stored in network servers, the issuer only gets confirmation that authentication is successful, the issuer doesn’t authenticate itself

This is how networks are shifting control of the authentication step to themselves. Here’s how the flow works:

Mastercard Passkey utilizes cryptographic keys that sit behind a biometric authentication layer (this is face ID). How does this work?

When the customer sets up their passkey, they are required to set up their biometric ID, which is done using device APIs (Android or iOS APIs)

The biometric creds (which could be Face ID, fingerprints) are encrypted, and stored within the device, within something called a Secure Enclave. And at this time, a passkey is created, which is a public - private key pair. The Private key is stored within the device, and the Public key is stored in Mastercard / Visa servers.

At the time of authentication, the biometric creds unlock the access to the private key in device local storage, which then signs a challenge, and sends it to Mastercard servers, which compares it to the public key that it has, and confirms that the customer is who they say they are.

This meets the 2 Factor Authentication Framework through: 1) Something you have: Phone (where private key is stored) 2) Something you are: Face ID

After successful biometric authentication, the acquiring bank then sends customer encrypted details to the issuer bank via Mastercard rails which does backend checks (which do not require user input) to authorize the transaction. The issuer still performs fraud checks and approves or declines the payment based on its own criteria. But this is second level checks: primary check is done by Mastercard.

So this is promising because here the first level authentication of biometric credential & private - public key authentication is happening by a 3rd party, which is not the issuing bank. And since issuers are notoriously slow at innovating, by carving this out, it could help increase the speed of innovation. Not to say the Passkey method is perfect, it currently involves multiple redirections, and it’s definitely not a seamless process today but these are things that can be worked on.

Note: A key point to note here is that Mastercard / Visa do this through a protocol called WebAuthN, which is the web standard for enabling passkey flows, and so this authentication can happen via browser as well. This is different from UPI, where the authentication flow is very tightly coupled with the device (SIM + device binding, and the CL embedded in the mobile app).

Now, how do we apply this to Biometric payments?

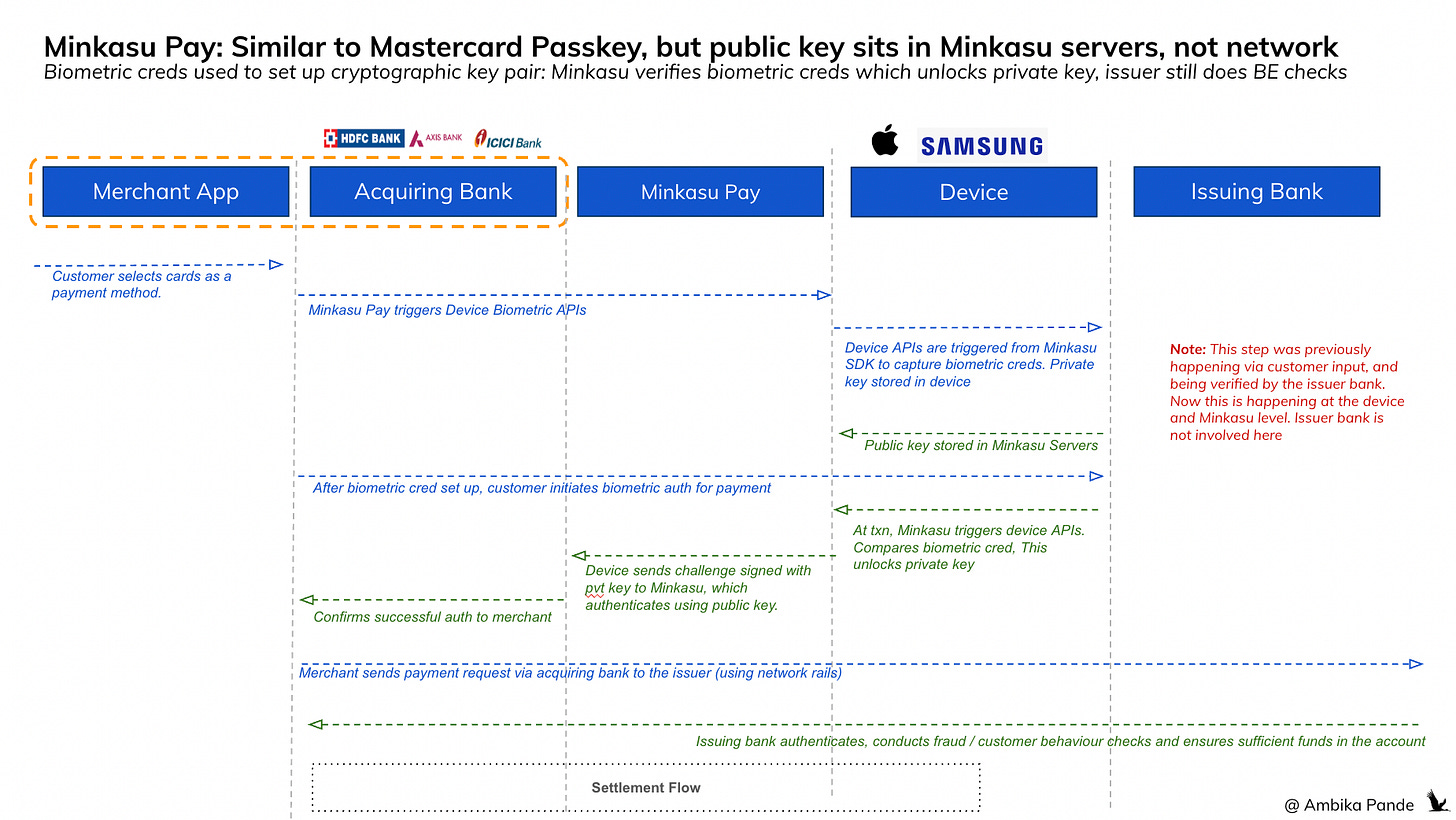

Well, there are two ways to do biometric payments, and how Minkasu Pay & Federal Bank have done it, and how NPCI may be planning to do it. Both will require some sort of passkey method.

One way is how Mastercard & Visa did it. Through passkeys, and the bank doesn’t authenticate itself, but just gets a “success” / “failure” response from the network

The second way, and this is something that I talked about in my previous article is where the public private key is still generated, but instead of the network storing the public key in their servers, and sending a successful auth response to the issuer bank, in this case, the issuer bank itself will store the public key, and authenticate the cryptographic challenge

The Minkasu Pay & Federal Bank Partnership for biometric authentication, this seems to be more cards focused:

Similar to Network Passkey, except here, Minkasu Pay stores the public key, not the network. To read the patent filed by Minkasu Pay, click here. What it clearly seems to call out is that the public key is stored in Minkasu Pay’s servers, which is referred to as the Secure Payment System. It was granted this patent in March 2024.

A. First-Time Setup

The user initiates a card-based payment. As part of the flow:

They're authenticated using traditional 2FA: OTP / CVV / PIN.

Then, Minkasu Pay SDK triggers the device's biometric API

At this point:

The biometric template is encrypted and stored by the OS, not by Minkasu. It’s stored in secure hardware and never leaves the device. Minkasu or the issuer never sees the biometric data.

The device generates a public-private key pair using its secure hardware (Secure Enclave or Android Keystore).

The private key stays on the device, protected and non-exportable.

The public key is sent to the Minkasu Pay servers

B. Repeat Use

Next time the user pays:

They choose biometric authentication.

The device’s biometric API is invoked by the Minkasu Pay SDK to capture and verify the face/fingerprint.

If matched:

The device unlocks access to the private key.

A cryptographic challenge is signed by the device using that key.

This signed challenge is sent to the Minkasu Pay, which:

Validates the signature using the public key it stored earlier.

Confirms the user’s identity and sends authentication success to the issuer bank

The issuer bank then conducts any backend risk & fraud checks and authorizes the payment, communicates the same to the acquiring bank & merchant via the network so that the transaction is logged, and is included in the daily settlement.

Similar to passkey, except here instead of the network, Minkasu Pay is playing the role of verifier. This is not network centric. I also assume that since there is a Mobile SDK involved, at this stage it is still primarily mobile based, unlike Mastercard / Visa, which can enable this through browsers

Unlike network-centric approaches, here Minkasu pay is the 3rd party that verifies the cryptographic signature. In the Network Passkey approach, Mastercard / Visa is authenticating the challenge using the public key stored in their servers, and informing the issuer of successful or failed authentication. However, since this is through a SDK embedded in the app, I assume that this is primarily mobile based, and cannot happen through a browser just yet.

This flow is actually very interesting to me, because if this takes off, it rewrites who provides authenticate services to the bank. Originally

The issuer bank was doing all the checks itself

The network (such as Visa / Mastercard) did do fraud checks, and it has been involved in authenticating payments, so them coming in and wanting to own this layer still makes sense

Minkasu Pay coming in with this opens this up to non issuer & non network players. Essentially it says: hey, just completely decouple the authentication part from payments. It’s one step beyond the bank ACS, because the bank ACS is deployed in the bank infra. Minkasu Pay servers are separate.

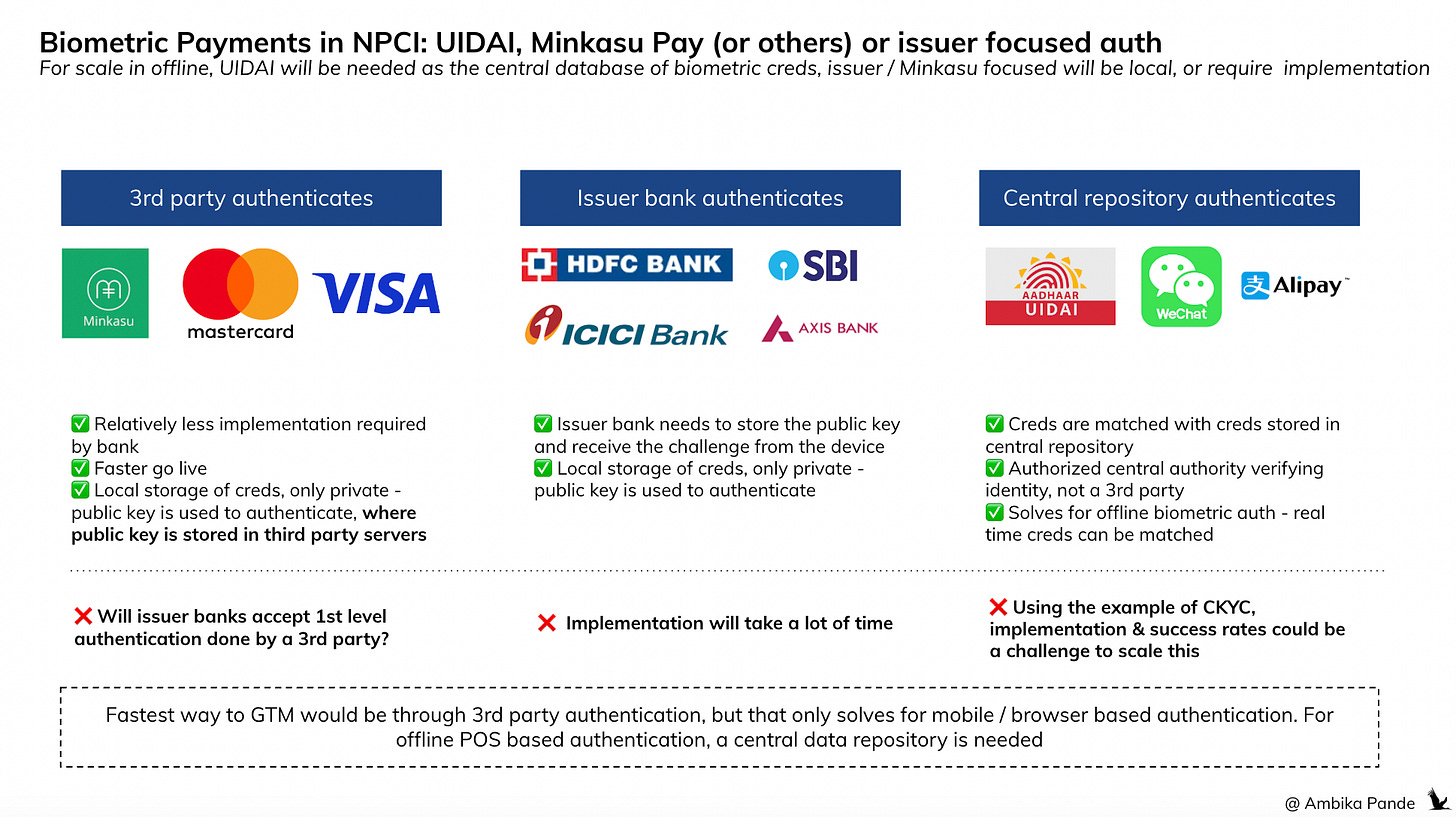

Biometric payments is something that reportedly NPCI is also considering now

You can check out the news details here:

Just like global networks like Visa and Mastercard, NPCI is now exploring alternate authentication methods beyond the traditional UPI PIN. But this shift is about more than just convenience, it signals a move away from SIM and device binding as the core method of identity verification. By leveraging biometrics stored locally on the device, the authentication framework begins to shift. The device itself (where the biometric key resides) satisfies “something you have”, while your biometric credential (fingerprint or face ID) satisfies “something you are” in 2FA.

What I expect to see here is, the Device APIs, local storage, and generation of the private & public passkey remains the same. What changes is who orchestrates this, and who stores the public key.

1. Get the issuer bank to make changes. Good luck everyone

This is where the issuer bank itself makes the changes to be able to receive and store the public key. May happen eventually, but as of now, seems very unlikely. I’d say we’re a few years away from this.

2. Do it through a Minkasu Pay type solution, remove burden of auth from issuer

The launch of Minkasu Pay with Federal is promising. However, Federal is a bank that in the past has been open to partner with fintechs & come up with innovative solutions. It’s also a challenger bank, which is probably why it is more open to these sort of plays. A key question that I still have here:

While this is easier to do via a SDK solution, or a 3rd party solution since it requires limited changes from the bank, apart from some response handling. Storing a public key and comparing signed challenges will require a lot more changes, is this something that a bank is even willing to offload?

3. Do it using a central repository of biometric authentication (ex: UIDAI)

India has a central biometric cred repository. UIDAI. Also the entity behind Aadhar. In this flow, again, the issuer would receive a “success” or a “failure” message from a 3rd party, but here, the verifying authority wouldn’t be a random 3rd party (like Minkasu), but a central authority. How would this work?

Similar to the existing flow. I’m assuming device APIs would be invoked to capture the user biometric data

Since here, the biometric data itself is being compared, this data would have to be shared in some encrypted form to UIDAI servers.

Some sort of public - private passkey set up, where the data is encrypted using the private key, and the public key is stored in UIDAI servers? Not too sure how this is being thought of, but this is one way I can think of it happening.

Also, to use UIDAI for any sort of biometric auth flow, the entity needs to have a AUA (Authentication User Agency), or KUA license (KYC User Agency). From what I understand, this isn’t easy to get, since this is pretty sensitive information. According to the UIDAI website, there are ~90 government entities that are AUAs / KUAs & about ~92 private entities that are KUAs.

But my misgivings arise with the fact that this isn’t very seamless at all.

First, any government portal (I’m not even going to go into my woes with EPFO) is a pain to use. Just to log-in requires the patience of a saint, and the understanding that from start to finish, by the time you’ve logged in, generated a new password, received an OTP, it’s a half day process) I don’t expect UIDAI to be any more seamless than current government portals. So - already, I’m seeing high failure rates, latency etc. Kind of how like CKYC was supposed to solve for KYC but failed miserably (with success rates < 60%, is what I heard).

People set up their Aadhar more than 10 years ago. I know I did, and what I looked like then is very different. It’s unlikely that biometric authentication using my Aadhar creds is going to be approved by anyone. And I’ll wager that this is the case with a lot of folks. And as mentioned in the previous point, updating this is….. well you’re better off just paying using a PIN or OTP flow. Lets leave it at that.

Central storage is always a greater privacy risk. That’s why almost every biometric flow (that I’ve researched atleast) happens through local storage → even if one user’s data is compromised, it doesn’t impact the entire database. Anywhere there is central storage is also attacked by hackers as a target

So keeping all this in mind, the easiest way to do this would be to use a Minkasu Pay sort of flow to orchestrate it. That’s because:

Minimal changes required from the issuer bank

You’re not held back by the woes of using a central government database

But do biometric payments even move the needle? Overall, there are fraud use cases, and in offline, it may improve CX, but implementation in India will be a big challenge:

I’m still thinking through about the value add of biometric payments, from a business perspective. The fraud use case is validated. But can it move the needle in other ways? And is it more in online, or offline? Both, or neither?

Well, online is still pretty seamless, even without biometric payments. Especially with tokenized cards, and UPI payments, it’s really only 1 step, entering the OTP or entering the PIN. So in online, unless this is a fraud play, I don’t see how the experience can be significantly improved through a biometric auth play.

And in offline, it may improve experience, in terms of long queues. But again, if a user has gone to an offline shop, picked up items, and is at the register, they’re a very high intent customer. Very unlikely that they’ll go away, even if the queue is very long. And since the cost of this device is to the business, if this doesn’t drive business, why would they invest in it?

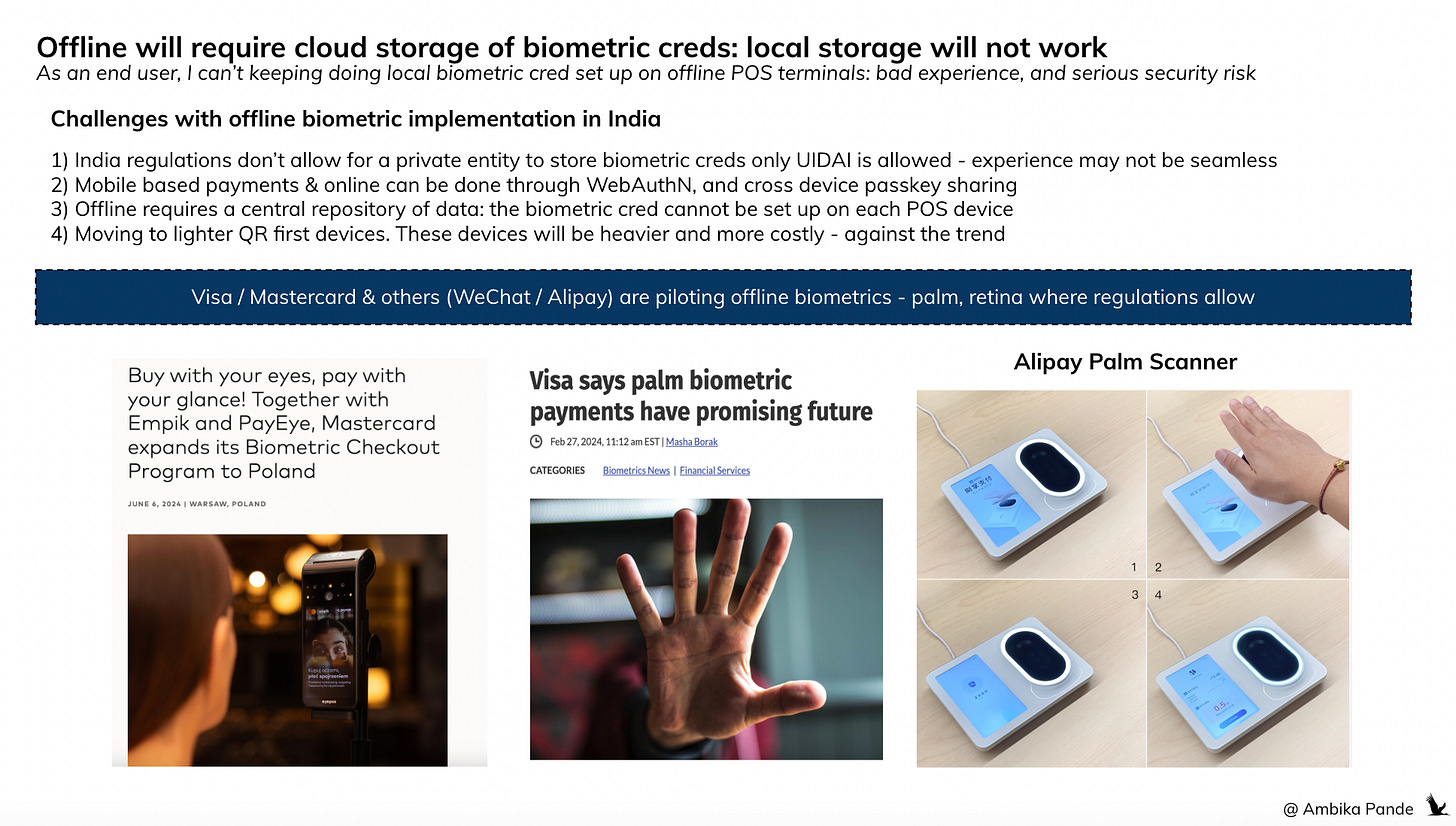

So just from an experience perspective, I don’t know how much this really moves the needle, both from an online & offline perspective. In fact, for offline, it seems to go against the trend of lighter, QR first devices

In offline, there is another angle. We’re actually moving away from heavier POS devices, to more lightweight, QR first, cheaper devices. A device which needs some sort of scanner to capture biometric creds actually moves in the opposite way.

From an implementation perspective, I see it being way easier for mobile and online payments (local storage). Offline will require some sort of central data repository - either UIDAI which will have implementation issues, or a private entity will need to store this in its cloud, which will not be allowed in India

If you want to do offline, then you don’t want to be setting it up at every POS terminal. Ideally you want to set it up once, and then use that to pay wherever you go. So maybe that’s where the central government database comes into play. No need to set it up at all. But there are challenges here with UIDAI that I called out already.

The second way to do it would be a non government, cloud based storage. Like what WeChat or AliPay are doing, offline palm based payments. Where you can set it up, either through your mobile app, or at an offline device. The creds are stored in cloud storage. And then whenever an end user authenticates using biometrics, the cloud storage is used to authenticate the user. The difference is that both those entities are Chinese. The China governance structure is massively state controlled, and central architecture is encouraged.

Globally, Mastercard is experimenting with a biometric offline payments: storing palm prints in cloud storage.

This depends on the geography and what they have mandated for payment authentication. In India, Aadhaar biometric data (fingerprints, iris) must be stored only by UIDAI, no private entity is allowed to retain or centrally store it. Even AUAs / KUAs cannot retain biometrics post-authentication, they must discard them immediately after passing to UIDAI. Apparently Mastercard pilots are live in Brazil, and some parts of LATAM, but unlikely this will be be allowed in India anytime soon.

Overall: the challenges with biometric implementation for payments in India - be it central agency, experience, a “needle mover” for businesses, or just against the trend, seem to outweigh its benefits.

RBI’s payments vision may talk about adopting biometric authentication, but the ground reality tells a different story.

In practice, biometrics in payments is likely to remain a niche feature, not a mass-market shift. Its most credible role? As a step-up authentication layer, for example, if someone wants to approve a large-value UPI transaction (say, above INR 1L). But we have cards for that already.

Unless UIDAI evolves and becomes dramatically easier and faster to integrate with, (unlikely) for the cloud based server approach, to unlock the offline experience, biometric-based payment flows will stay clunky and compliance-heavy. That means mass adoption is unlikely.

You’ll see early adopters and pilots, like what Minkasu Pay is enabling, which is pretty cool but don’t expect that to scale across the UPI or card ecosystem just yet. For now, biometrics for payments atleast will stay an idea worth tracking, not a revolution in the making.

![[#59] From Card Networks to Credential Networks: Visa & Mastercard’s Next Big Move?](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!2Qj-!,w_1300,h_650,c_fill,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep,g_auto/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F33a1a425-c611-4765-a9d5-42ea1246d788_1456x817.jpeg)

Biometric Authentication itself has a lot of attendant risks.. There are false fingers, there are video replays, and many other means of attacks. PAD certifications are very important and these need even more "integrity" as the world of AI creeps in ! Happy to get into a more detailed discussion !

Insightful and extremely informative thank you.