[#66] E-commerce to fintech: A proven path. Fintech to e-commerce: Still a question

TPAP as a service players such as Juspay / Razorpay provide UPI / fintech know how, but the "e-comm as a service" ONDC platform has not scaled to provide the e-commerce plug-in experience for fintechs

Something interesting but not entirely surprising happened this week (June 2025): Flipkart secured an NBFC license.

For those tracking the space closely, this felt less like breaking news and more like an inevitability. The signs have been there for months if not years. Flipkart’s steady expansion into payments, credit, and now regulated lending is part of a broader shift that’s been quietly reshaping the ecosystem.

I’ve been exploring this theme for a while now: why e-commerce players are increasingly moving into fintech. But what’s even more interesting is the asymmetry, the reverse isn’t happening. Fintech-first players, especially UPI apps like PhonePe, CRED, and Paytm, have made multiple attempts to break into commerce. ONDC was supposed to be the unlock, but results so far suggest otherwise.

This piece explores the directional trend: why “ecomm → fintech” is working, but “fintech → ecomm” isn’t. And what that says about distribution, margins, and infrastructure in India’s digital economy

Let’s look at it from the ecomm to fintech lens and it makes perfect sense. Take Amazon as an example:

High volumes = big upside: Even a few basis points saved on massive GMV translates into significant absolute gains.

Own the full CX: Checkout and payments are critical to the user journey. Why let a third party control that experience?

Credit as a VAS: With millions of transacting users, offering embedded credit is a natural and high-value extension.

In short: Fintech isn’t just adjacent for ecomm it’s a logical, margin-boosting next step.

Amazon had already got the memo: It's a significant fintech + ecomm player in India and it was a strategic move to leverage its vast user base and transaction volume. Let's look at the chronology of how it went and acquired these licenses:

PPI license: March 2017. Allowed digital wallets, like a faux UPI App

UPI App: Feb 2019. Own control on in-app UPI payments

PA for domestic payments: Feb 2024. Control on checkout and the payment processing

PA-CB (import only): July 2024. This is for international sellers listed on Amazon India, so this license enables Amazon facilitated money flows from India → internationally. It’s surprising that they don’t have an export license, since this would enable money flows from international customers to India, but I suspect this will eventually happen

Axio acquisition (NBFC): Jan 2025. First invested $20M in August 2024 during its extended Series C round.

Now, Flipkart seems to be following a similar path:

PPI License: Flipkart acquired PhonePe in 2016, and through that got access to PhonePe’s PPI license. When Flipkart and PhonePe parted ways, and completed their separation in December 2022, then Flipkart lost this license, so currently it doesn’t have one.

Super.Money UPI App: March 2024 launch. Flipkart's UPI app, which has been spun off as a separate entity.

NBFC License: In June 2025, Flipkart acquired an NBFC license, enabling it to offer in-house lending services.

In one of my previous pieces, I had talked about how fintechs are going towards stack specialisation. You can check it out at the link (included further below) but TLDR: there seem to be 3 plays emerging:

a. The full stack fintech play, which includes online, offline, UPI App & infra. Take the examples of PineLabs (PineLabs POS, Plural - their online PA, Fave - their consumer app acquired in 2021, and Setu - which is their infra, AA, identity, data and insights acquisition, acquired in 2022)

b. You’ve got the standalone Xborder play: Example → Xflow, Briskpe, Payoneer, Skydo, Wise, which are only going after the PA-CB license

c. The third: The NBFC + PPI + UPI App play, which controls the funds for lending, the wallet which acts as a faux account, and the UPI App, which is the medium through which seamless payments are made. This is one play that can be super valuable to an ecomm play, and hence I feel it’s very possible that Flipkart goes after a PPI license again.

And that’s probably not all in terms of Flipkart’s fintech play. I’d say its highly probable that Flipkart goes after a PA license to handle domestic payment processing directly. In FY24 in fact, their GMV was ~$8.5B (INR 70k Cr). A 5-10 bps cost, at the very minimum can be ~50 Cr (or ~$7M). As a % this is not significant. But it’s probably less about the cost & more about the control.

And eventually a PA-CB license also. For PA-CB, I’d initially expect them to go for an export license, since it will solve for international customers being able to buy from Indian sellers. But the import license also makes strategic sense, since Flipkart does allow international sellers to list on its marketplace.

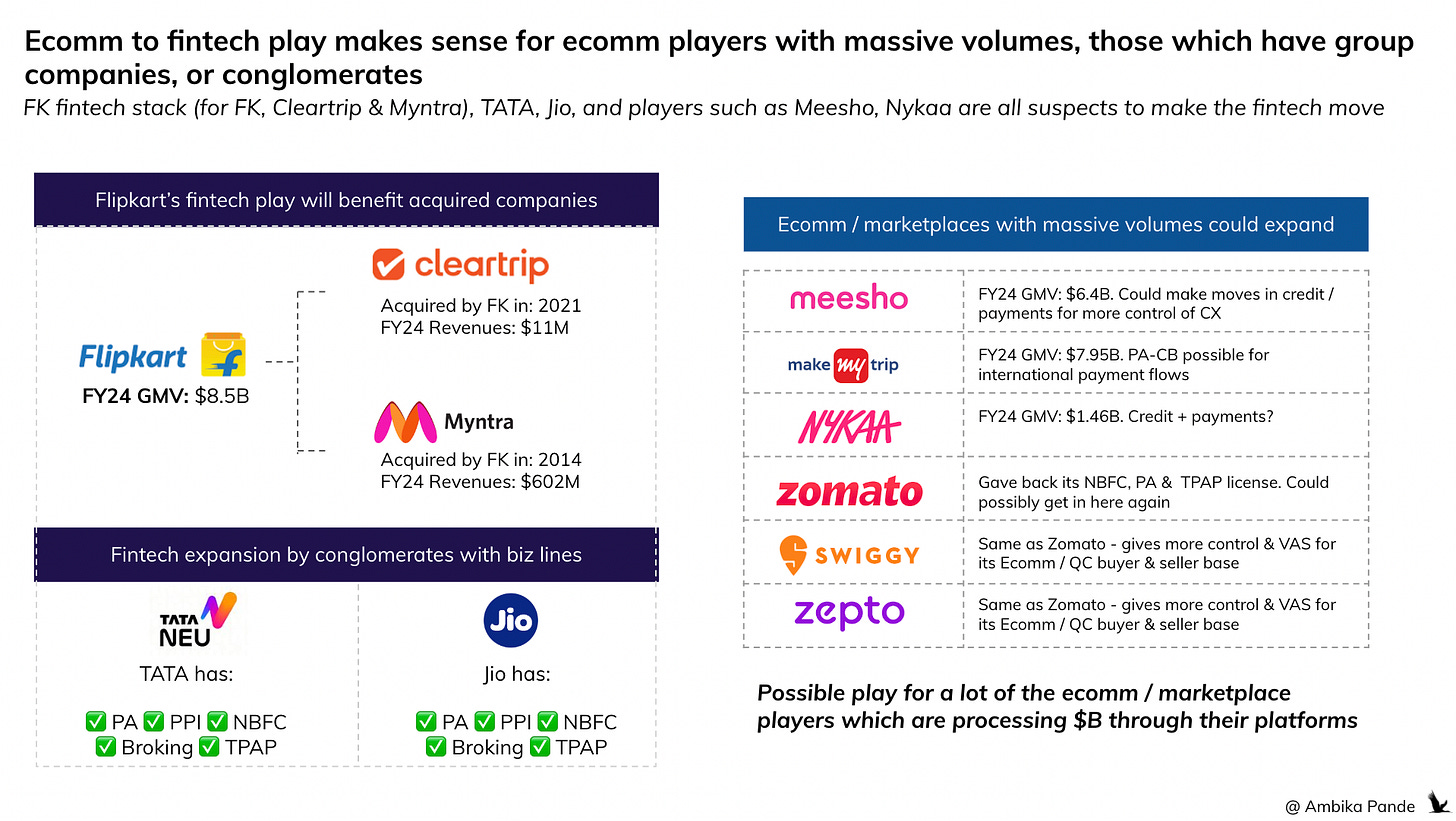

For Flipkart atleast, the benefits flow to its group companies:

Myntra: Acquired by Flipkart in 2014 for $240M, operates as a standalone brand. In 2024, hit a Monthly User Base (MAU) of ~70M. I couldn’t find their GMV details, but Flipkart’s ratio of revenue to GMV is ~25% (INR 17k Cr / 70k Cr in FY24). Myntra revenues in FY24 were INR 5122 Cr (~$602M). If I use the 25% number, the GMV comes to ~$2.3B, which is a significant value of payments being processed through the Myntra platform. I can see an in-house, or a group company payment stack adding value here

Cleartrip: Flipkart acquired Cleartrip in 2021. Again, not a clear view of GMV here, but its revenues in FY2024 were ~97 Cr. (~$11M).

You can check out my piece on fintech license aggregation and stack specialisation below:

[#63] Do all roads in fintech lead to license aggregation (Part 4): It's not about license aggregation, but stack specialization

Hi folks. Welcome back to the 4th edition of this sub-theme in my newsletter: Do all roads in fintech lead to license aggregation?

The bigger trend here? For large-scale ecomm players and consumer-facing conglomerates, getting into fintech isn’t optional it’s inevitable. Even if they don’t go full-stack, UPI apps or select fintech licenses become necessary tools for deeper ownership of the user journey.

As scale grows, so does the need for tighter control of checkout, of payments, of user data, of the full funnel. And that’s pushing ecomm into fintech. Here are some strong candidates already on this path, or likely to get there:

Meesho: FY24 GMV of $6.4B. Has enough volume & buyer / sellers to justify fintech extensions.

MakeMyTrip: FY24 GMV of $7.95B. High-ticket, frequent purchases make it a natural fit for credit, insurance, and UPI plays.

Nykaa: FY24 GMV of $1.46B. Premium D2C commerce, ideal for embedded credit and loyalty-led fintech features

Jio/Ajio: Already in deep. FY24 revenues of ~$1.1B. Owns a PA, PPI, NBFC, UPI app, and even broking via Jio-Blackrock.

Tata Neu: $470M in FY24 revenues. Tata Group already has all major licenses PA, PPI, NBFC, UPI, and broking.

Zomato: FY24 GMV of ~$5.63B. Had an NBFC, PA, UPI license but gave them up but may re-enter. Too much volume & a big enough marketplace to ignore this

Swiggy: FY24 GMV of ~$3B. Dabbled in UPI plugins; natural fit for credit or embedded finance as retention tools.

Zepto: ~$4B GMV run-rate in FY25. May hold off for IPO, but fintech infra will make sense soon after.

The bigger you are in commerce, the harder it is to ignore fintech. The margins are better, the control is tighter, and the customer value is stickier.

That’s why the ecomm-to-fintech trend is here to stay.

The reverse journey: UPI apps and PAs expanding into e-commerce or quick commerce seems plausible on paper. But so far, it hasn’t worked in practice.

The full-stack-ization of Indian fintech is no longer just a trend, it’s a necessity. What started as focused plays (consumer apps, B2B platforms, or infrastructure providers) is evolving into stack aggregation. As margins compress and growth slows, building end-to-end control has become the only viable path to sustained value creation.

One of the most ambitious (and risky) ways to beef up margins? Expanding into e-commerce. Several UPI apps: PhonePe, CRED, Paytm are now betting that adding commerce to their payments stack can unlock monetization and engagement. But without owning demand or supply, that playbook has its limits.

You can check out my article below, where I’ve talked about the full stack

The logic is, especially for a B2C UPI App is that “Hey! I have a captive user base. Why should I only facilitate payments? I can sell them other stuff!”

PhonePe tried this in a roundabout way with what it called the “PhonePe Switch.” Which was a marketplace that hosted apps within the PhonePe App. Think of it this way: instead of going directly to Zomato to order food, you could now access the Zomato App WITHIN PhonePe. And so on. I don’t think this really scaled.

PhonePe then tried this with Pincode, which is a buyer side app powered by the ONDC network, focusing on hyperlocal deliveries, and directly competing with the Blinkit’s and the Instamart’s of the world. This made ~INR 3 Cr of revenue in FY24, which is a blip in PhonePe’s overall FY24 revenues of INR ~5064 Cr. And this hasn’t really scaled up eother

Paytm tried to go the fullstack way, through Paytm Mall in 2017 which they scaled down in 2022: They tried to do this in a partial way - not exactly fullstack like Amazon & Flipkart, but more of a marketplace, with dependencies on 3rd party logistics & seller owned logistics. This didn’t scale, and eventually Paytm scaled this down in 2022.

There are other examples. Whatsapp is partnering with Jiomart to power an in-app flow, where inventory discovery, and payment can happen within Whatsapp using conversational bots. This has seen limited rollout till now. Reportedly Gpay is also trying something with ONDC but I couldn’t find sources to back this or anything on the Gpay app. So I’m assuming nothing (significant) has happened.

Of course, it’s possible that the idea was right but the timing was off. But looking at how these attempts have played out, that feels increasingly unlikely. While we’ll continue to see pilots and experiments, the jury is still very much out on whether UPI-first apps can build a compelling e-commerce value proposition that drives real user stickiness.

What seems more plausible is the reverse direction: existing e-commerce or B2C brands (like Groww, for instance) adopting UPI to enhance native experiences and deepen engagement. But so far, the thesis that UPI apps can scale into ecomm just hasn’t delivered convincing proof on product-market fit or retention.

Note: I’ve used UPI Apps here as an example, because they are usually the player in fintech that has the customer base. PA players such as Razorpay, CC Avenue, Pine Labs that have already or are reportedly evaluating plays into the consumer app side of things could also get into ecommerce, but till now, that hasn’t happened. They’ve stayed on the fintech / full stack side of things, where even though they have the merchant base, they’re building more VAS for the merchants to help them run their business (ex: fraud / risk modules, credit marketplaces, the CFO stack and so on)

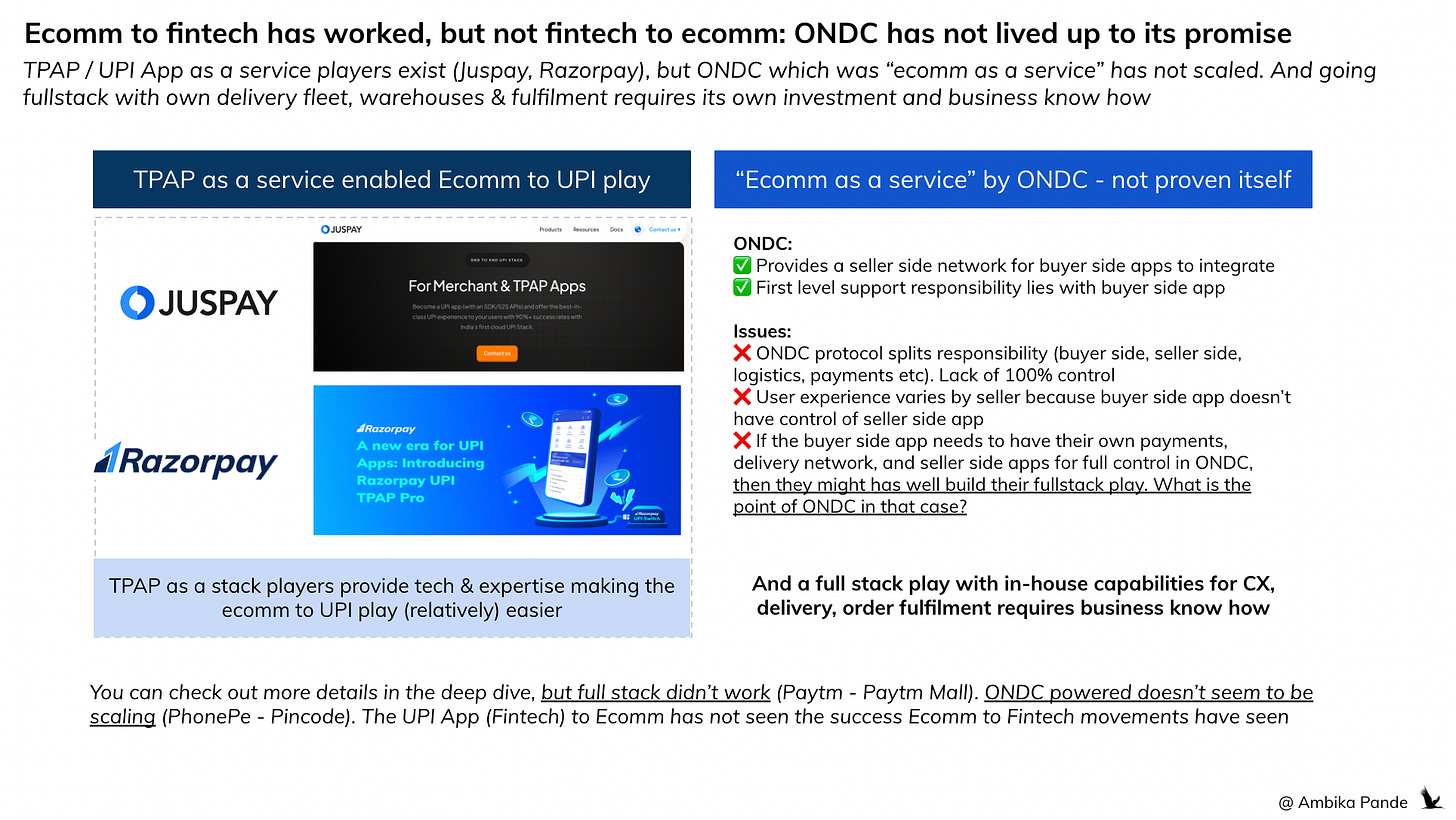

The reason for the lack of success of UPI App to Ecomm movement is because there are players that provide a “TPAP as a service play,” but the opposite - the “Ecomm as a service” play which ONDC was supposed to solve has not happened

From a checkout experience standpoint, PAs like Razorpay offer multiple integration models. One common option is server-to-server (S2S) integration, which allows merchants, especially e-commerce platforms to fully own the front-end UI/UX of the checkout flow, while using the PA’s infrastructure purely for backend payment processing. This provides a cleaner, brand-controlled experience for customers without directly handling compliance-heavy money flows.

To perform the actual settlement of funds, however, the underlying payment processing must be routed through a licensed PA. Large e-commerce players like Amazon have either secured PA licenses to own the end-to-end payment stack, giving them more control, data visibility, and margin optimization. But this is often a strategic move viable only for very large platforms with the resources and scale to justify the compliance and operational overhead. For mid-size and smaller players, S2S or SDK-based integrations with licensed PAs provide sufficient control over user experience, without the need to directly hold a PA license. In most cases, this strikes a practical balance between control and compliance.

These players may prefer more ownership on a part of the payment process, which is consumer app / UPI, which has already started happening.

The “TPAP-as-a-service” model is enabling ecomm → UPI:

E-commerce players entering UPI don’t have to build from scratch. Companies like Juspay now offer TPAP infrastructure as a service, making it easier for ecomm apps to plug into the UPI ecosystem. While the platform still needs to secure its own TPAP license, the technical heavy lifting: like API integrations, bank partnerships, and compliance scaffolding is handled by domain specialists. In short, in UPI, there are subject-matter experts who can abstract the complexity. This has made “ecomm to UPI” a far more viable path.

But the reverse: “ecomm as a service” hasn’t scaled, despite ONDC’s initial promise:

ONDC was designed to offer a plug-and-play ecomm layer: letting any app become a buyer-side interface, and any merchant integrate via seller-side platforms. In theory, this modular approach should’ve made it easy for UPI apps to expand into commerce. But in reality, the ONDC experience remains fragmented and low-quality. Unlike payments, which are single-shot transactions, ecomm needs deep control over supply chains, merchant onboarding, logistics, returns, and customer experience. There’s no player owning the full stack, and placing interoperability above user experience has backfired. Three years post-launch (since 2023), success stories are rare: Juspay’s Namma Yatri being the exception, not the rule. The result: “UPI app to ecomm” remains a narrative with little traction or proof of scale.

What’s the ONDC story - and why is “Ecomm as a service” not set up for success?

ONDC has not scaled up as some folks expected. I always had my doubts, and you can check out the piece I wrote on this ~1 year ago.

ONDC was envisioned as a way to level the playing field for smaller merchants by breaking the monopolistic hold that marketplaces like Amazon, Flipkart, Zomato, and Swiggy have over pricing, discovery, and seller visibility. While the intent is noble, the model has been plagued by operational fragmentation, with the biggest flaw being the lack of centralized experience ownership.

What traditional marketplaces offer and what ONDC fails to replicate is end-to-end control: from customer acquisition, product discovery, payments (often via their own PAs or UPI apps), credit, to customer service and fulfilment. ONDC, by contrast, is built as a network of interoperable players, but with no single entity responsible for the customer journey.

Here’s how the ONDC flow typically works:

Merchant onboarding happens through Seller Network Participants like Mystore, where sellers must complete KYC, upload catalogs, configure payments, and manage inventory.

Buyer discovery takes place on Buyer Apps like Pincode (by PhonePe).

Order fulfilment is handled by ONDC-integrated logistics players like Ekart, Shadowfax, Dunzo, etc.

Payments are routed via approved Payment Aggregators like Razorpay or Paytm.

Customer support and refunds crucially are escalated to ONDC if the buyer side apps are unable to solve first level escalations since no single entity owns the transaction lifecycle.

The missing piece is clear: centralized orchestration. Without a player taking accountability for the full customer experience, ONDC’s promise of democratizing e-commerce feels incomplete. In theory, this model should have triggered massive growth for ONDC-powered apps, challenging traditional marketplaces. But that hasn't happened.

Just look at the numbers: ONDC volumes remain a fraction of what Flipkart, Amazon, Swiggy, or Zomato clock daily, let alone monthly. Until someone steps in to "stitch the stack" and take ownership of quality, support, and fulfilment, ONDC will continue to struggle with scale and stickiness.

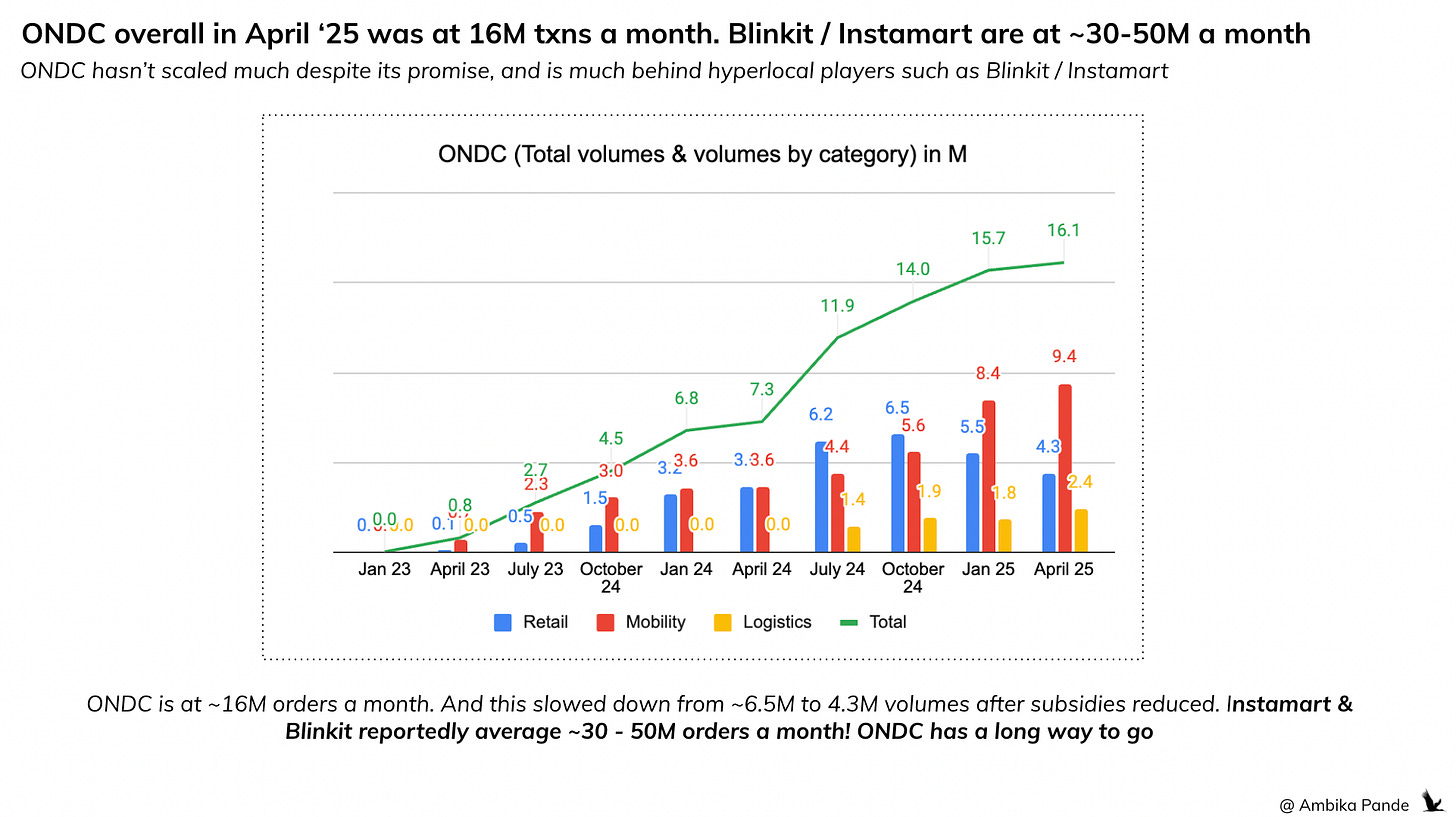

Source: ONDC website

As of April 2025, ONDC is clocking 16.1 million transactions a month—but the majority of that is driven by mobility use cases like Namma Yatri. Retail, which was once the poster child for ONDC, has actually declined: it peaked at ~6.5M transactions in July 2024, but has since dropped to ~4.3M in April 2025. The likely reason seems to be subsidy cuts, down from ₹2.5 Cr/app to ₹30L/app. Logistics volumes are growing steadily, but there’s no exponential spike here.

Now contrast that with traditional marketplaces: Zomato alone has ~21M monthly users, many of whom order multiple times a month. Blinkit and Instamart were averaging 1–2 million orders per day in 2024, which adds up to 30–50 million monthly transactions. So ONDC has a way to go & has to add a lot to its value proposition to incentivise participation. It was pitched as an existential threat to the ecomm marketplaces. The numbers tell the opposite story, it doesn’t seem like the ecomm players are bothered.

And honestly, it’s not hard to see why ONDC has not scaled. As a customer, I care about:

My order arriving on time

A seamless resolution when something goes wrong

A smooth, predictable experience

What I don’t want is to email multiple providers and escalate to ONDC just to find out where my order is or get my refund figured out, because the seller policy is not standardized.

Until ONDC solves for end-to-end accountability, it’s unlikely to rival the scaled, reliable experiences of Flipkart, Zomato, or Swiggy.

To be fair, Pincode (by PhonePe) does attempt to improve the ONDC experience by taking more ownership than other buyer apps:

What Pincode does:

First-level issue resolution: It handles common issues (delays, refunds, non-delivery) within the app: no redirection to seller or delivery partner creating a more Amazon-like UX. It’s only if the issue is unable to be resolved, or if its a broader seller level issue - then the customer has to raise a complaint to ONDC.

Partial control on delivery: PhonePe has started using its own fleet in select areas, alongside partners like Shadowfax, LoadShare, Dunzo, helping maintain SLAs and delivery quality.

What Pincode doesn’t do (yet):

No direct seller onboarding: It relies on seller apps like Mystore or uEngage, meaning no control over catalog quality, pricing, or inventory. If Pincode builds its own seller app, it might as well become a full-fledged ecomm marketplace defeating the point of plugging into ONDC. Which atleast, if we look at Paytm & Paytm Mall’s example hasn’t gone well in the past. Maybe PhonePe could pull this off - this is something that time will tell

No full-stack fulfillment: It doesn't own logistics end-to-end. Returns, replacements, and service levels still depend on fragmented seller/logistics performance.

Bottom line: Without full-stack control, ONDC’s value prop weakens and so does the case for UPI apps to scale into ecomm through it.

Because ONDC splits responsibilities across buyer apps, seller apps, and logistics providers, there’s no end-to-end ownership. Apps like Pincode try to improve UX with overlays, but they can’t guarantee consistency.

You get: Catalogue mismatches: different images, SKUs, and prices across seller apps. There can be inventory issues due to fragmented systems & no ONE source of truth across inventory stores, because sellers are not owned by the buyer apps, and can be onboarded through multiple seller apps. There can also be returns/refund issues which vary by seller, with no unified policy like Flipkart or Amazon

Until this disjointed experience is fixed, the “ecomm-as-a-service” model won’t work. And without that, UPI apps can’t easily plug into ecomm, making their expansion story far more difficult.

![[#63] Do all roads in fintech lead to license aggregation (Part 4): It's not about license aggregation, but stack specialization](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!wgzi!,w_280,h_280,c_fill,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep,g_auto/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F5999ec49-5d06-47a1-b37f-53a5ba1f8965_1946x1090.png)

![[#60] The UPI Dilemma: What happens when the infra and the apps are commodities?](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!lwZZ!,w_140,h_140,c_fill,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep,g_auto/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2Fa696dca4-050f-4c95-80a7-c6e9129ce3ee_1906x1070.png)

![[#17] ONDC - What’s the Catch?](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!Eovs!,w_140,h_140,c_fill,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep,g_auto/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2Fe727bc04-cdd7-4464-8d7e-274916a28c1a_900x512.png)